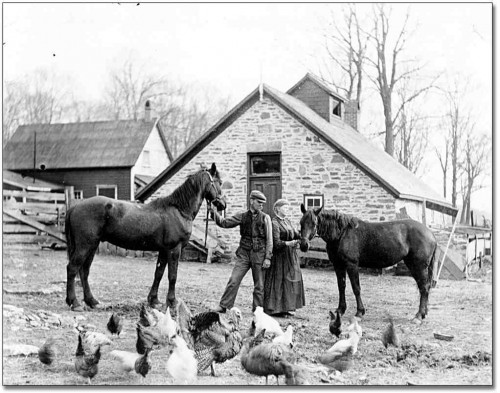

“Growing up in a conservative Christian home on our beyond organic family farm in the 1960s, I lived in two different worlds. Our church friends lived in one world, but our family farm lived in another. My Dad and Mom, ultra conservative by any standard, routinely befriended hippies and our house often had dope-smoking mother-earthers hanging around talking about compost, dome homes, and Viet Nam war atrocities.

On Sunday, of course, I spent the day with straight-laced Bible fundamentalists who made jokes about hippies and those mother earthers. When Dad made Adelle Davis’ Tiger Milk, a concoction of brewer’s yeast, honey, raw milk from our Guernsey cows, and I can’t remember what else, our church buddies called it Panther Puke. I grew up on Bible memory programs and Mother Earth News magazine.

While our church friends made jokes about environmentalists, in our house The Whole Earth Catalogue stimulated many great discussions. Our family routinely patronized the health food store when it first came to town, a place our Christian friends thought cultish. How could a Christian patronize a place that smelled like incense, sold tofu, and had Zen literature stashed about? Our Christian friends built Tyson chicken houses and confinement dairies, used pharmaceuticals indiscriminately and poured on chemical fertilizer. Even their backyard gardens received liberal (a judicious use of the word liberal, to be sure) doses of insecticide just to be safe.

The whole notion that farming and food systems could contain a moral implication couldn’t make it past the laughter and jokes about environmentalist pinko commies. Yet our family plugged on, eschewing chemicals, building compost piles, planting trees, and attending environmental farming conferences. As our farm began attracting attention, most visitors were tree-hugging cosmic nirvana creation-worshippers. We used these visits to plant seeds of Biblically-based stewardship as Creator-worshippers. That sure made for some interesting conversations.

Over the years, I’ve seen an amazing transformation in our farm visitors. Today, probably half are conservative home-schooling Christians. I believe that the home-schooling movement spawned an entire awakening to alternative ideas. Families who left the conventional institutional educational setting, who disagreed with credentialed officialdom, found their new path soul satisfying. That satisfaction led them to ask the question: “Well, I wonder what else I’ve been missing out on?”

This quest for a narrow way within a broad way cultural context led families to chiropractors (what, those quacks?), nutrition, cottage-based businesses and home-based self-reliance. The home school idea literally sprouted kitchen sprout growing, raw milk consumption, gardens, and domestic flour mills for home-baked breads.

I believe the Christian community, which should have been the repository of “fearfully and wonderfully made,” squandered this high moral ground of environmental stewardship. Today, young people like Noah Sanders are beginning to chip away at the stereotype of the creation-exploitive (just one notch below rapist) religious right. When members of the religious right espouse creation stewardship, people listen to the Biblical redemption message who would never give it a thought otherwise.”

– Joel Salatin, from the introduction to Born-Again Dirt: Farming To The Glory Of God, by Noah Sanders.

Not much to be added to these robust sentiments. I’ll simply say that I love Salatin’s freehanded use of a diverse range of time capsule language. Still can’t believe that Christianity could get so far away from caring about the earth, but there are about a million things I can’t comprehend about the history of Christianity.