“What the world expects of Christians is that Christians should speak out, loud and clear, and that they should voice their condemnation in such a way that never a doubt, never the slightest doubt, could rise in the heart of the simplest man. That they should get away from abstraction and confront the blood-stained face history has taken on today. The grouping we need is a grouping of men resolved to speak out clearly and to pay up personally. . .

———-

And now, what can Christians do for us?

To begin with, give up empty quarrels, the first of which is the quarrel about pessimism. . .

If Christianity is pessimistic as to man, it is optimistic as to human destiny. Well, I can say that, pessimistic as to human destiny, I am optimistic as to man. And not in the name of a humanism that always seemed to me to fall short, but in the name of an ignorance that tries to negate nothing.

This means that the words “pessimism” and “optimism” need to be clearly defined and that, until we can do so, we must pay attention to what unites us rather than to what separates us.

———–

We are faced with evil. And, as for me, I feel rather as Augustine did before becoming a Christian when he said: “I tried to find the source of evil and I got nowhere.” But it is also true that I, and a few others, know what must be done, if not to reduce evil, as least not to add to it. Perhaps we cannot prevent this world from being a world in which children are tortured. But we can reduce the number of tortures children. And if you don’t help us, who else in the world can help us do this?

. . .It may be, I am we’ll aware, that Christianity will answer negatively. Oh, not by your mouths, I am convinced. But it may be, and this is even more probable, that Christianity will insist on maintaining a compromise. . .Possibly it will insist on losing once and for all the virtue of revolt and indignation that belonged to it long ago. In that case Christians will live and Christianity will die.”

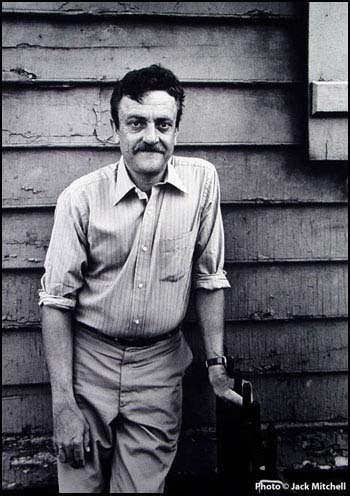

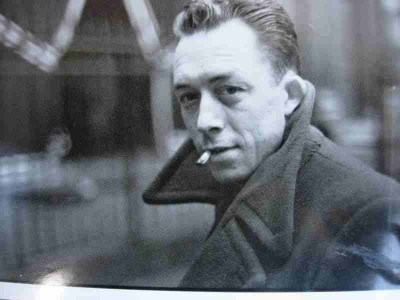

– Excerpts from Albert Camus The Unbeliever And Christians

__________

In Part I, Camus opened this lecture with his own gracious disclaimer on Christianity.

Camus gave this lecture in 1948, in the wake of WWII. As a humanist and also a passionately moral man, his calls to action were built upon wreckage of the war and the seeming ambivalence of the church at large to the world’s suffering. He calls to question whether a Christian should be so preoccupied with the eternal question that he disregards fighting for goodness here on earth. His discerning insights into the proper out-workings of this faith and his willingness to take on the same harsh implications of the role of outspoken defender of the weak are something powerful to behold.